End of the Blockade, Start of a New War of Nerves

Stalin concluded his Berlin strategy was not paying off at the end of January 1949. By that date, liquid fuel was being delivered at rates unknown before, coal reserves were no longer being drawn down, and the standard food ration in West Berlin had been increased by more than 15%. Under the circumstances, Stalin faced the fact that his last Ally, General Winter, had abandoned him. On January 30 he sent an arcane message to the West signalling his willingness to re-open negotiations about the situation in Berlin.

It was not until March, however, that the superpowers started groping their way slowly toward the lifting of the Blockade. The negotiations were so secret that not even General Clay knew about them, and the British and French were not let in on the secret until March 21. Even those involved in the exchanges were so burned by Stalin’s duplicity that they did not trust the talks to produce results. The two air forces actually flying the Airlift were kept in the dark and planning to maintain the Airlift for two, three or even ten more years.

The success of the Airlift meant that the Allies were negotiating from strength. They refused to stop either the establishment of a sovereign German state or the creation of a Western defensive alliance (NATO). The only concession they made was to agree to a meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers.

Meanwhile, the torturous process of drafting a German constitution had also continued. A draft was agreed upon on April 25, 1949, and the date for presenting it to a plenary session of the Parliamentary Council was set for May 15. In the event, the Parliamentary Council approved the “Basic Law” ahead of schedule on May 9, 1949. The way to the establishment of an independent West German state was now free. The importance of this cannot be overstated. This was the key development that Stalin had been trying to prevent when he imposed the Blockade — and it was the one thing he most wanted to prevent by offering to lift it as well. Yet by the spring of 1949, Stalin had so overplayed his hand in Berlin that the West was inflexible. By 5 May a deal had been struck and a public announcement was made that the Blockade would end 12 May.

The reaction in Germany, particularly in Berlin, was cynical rather than joyous. Neither the Occupation Authorities nor the Berliners trusted the Soviets. The Occupation Authorities had the added burden of trying to work out all the practical details not covered in the political agreements. Nothing had been agreed about currency, for example, or electricity. Nevertheless, plans went ahead for road convoys and trainloads of supplies to set out for Berlin at one minute after midnight on the morning of May 12.

The Soviets showed their hand just one day after the announcement by imposing arbitrary restrictions on the movement of goods by surface transport even before it had resumed! They insisted that all trains were to be pulled by East German locomotives and manned by East German personnel. Furthermore, there was a maximum limit set on the number of trains per day: 16 goods trains and 6 passenger trains. Thus, although the lights came on again in West Berlin at midnight May 11 and barriers on the autobahn came down one minute later, no one in Berlin trusted the “peace.”

What this meant for the Allies was that the Airlift was maintained at full throttle. It did not miss a beat – or take-off and landing, in this case. To be sure, supplies of additional goods might now be flowing into Berlin by road, raid and canal, but the Western objective was to build up reserves of all necessities in the city in anticipation of the next Soviet blockade. The expectation was that it might come sooner rather than later – if the Council of Foreign Ministers didn’t go the way the Soviets wanted. The general consensus was that it was necessary to build up a five to six-month reserve of supplies and above all retain the institutions and organisations for running an Airlift intact even after that goal had been attained. Plans called for the resumption of full Airlift operations if and when the Soviets re-imposed a Blockade.

The Berliners’ fear was even greater. They feared that after all they had gone through and all the determination they had shown for the sake of political freedom that the West would still “sell them down the river” at the Council of Foreign Ministers. Unfortunately for them, there was nothing they could do but watch and wait.

The Council of Foreign Ministers, which convened in Paris on May 23, 1949, however, turned out to be nothing more than a warmed-over re-run of all previous Councils of Foreign Ministers. The Soviets first condemned the new West German constitution as “monopolistic capitalism,” the Federalist structure was called “Hitlerite centralism” and majority decision-making was “non-democratic.” In short, their commentary was pure ideological drivel without content. Rather than sovereignty under such an “oppressive” constitution, the Soviets suggested that the Germans should be returned to “Four Power” government – where the Soviet Union had a veto on everything. Dean Acheson allegedly summarized the Soviet position as meaning that “everything in Berlin would require Kommandatura approval except dying.”[i]

The best that can be said for this final meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers is that it convinced the West that they had acted correctly by introducing a sound currency in their Zones and moving forward with an independent West German State – and that they were wise to continue to build up reserves in Berlin. In the second half of July, both the British Cabinet and the American Security Council approved keeping two RAF transport squadrons and two USAF carrier groups respectively stationed indefinitely in Germany.

It was a wise decision. Already the Soviets were showing their muscle on the surface routes. Trains were routinely turned back for “technical difficulties.” Lorries carrying supplies for the civilian population were turned back because the autobahns were suddenly only open for supplies intended for the Allied garrisons. Rolling stock was arbitrarily impounded. Mail was confiscated wholesale, and it became impractical to send it by surface at all. When the railway workers went on strike demanding payment in West Marks, re-instatement of fired workers and recognition for their independent (not SED-controlled) union, the city of Berlin was again almost totally dependent on the Airlift for another 38 days.

Meanwhile, the SED officials insisted both publicly and privately that the lifting of the Blockade was just “temporary.” They claimed it had been undertaken only to clear up some “bottlenecks” in East German production resulting from the counter-blockade – a back-handed admission of the comparative failure of the Eastern economy. The SED assured its constituents that the Blockade would be re-imposed just as soon as these “technical” difficulties had been overcome.

What was even more alarming, the Soviets increased fighter activity in the corridors and “unilaterally” narrowed the corridors from twenty to nine miles. The Western Allies ignored the latest unilateral “directive” just as they had ignored earlier ones about filing their flight plans in advance with the Soviet authorities. Nevertheless, the signal was ominous.

Nevertheless, the phase out of the Airlift started in the first of August 1949, when the U.S. Navy squadrons and the USAF Group at Celle ended their operations and returned home. The British government started to let contracts with the civilian charter companies expire and on 16 August the last civilian flight on the Airlift was logged. The last Airlift sortie by an RAF York took place 26 August and the last Airlift sortie by an RAF Hasting was flown 6 September. In the meantime the Combined Airlift Task Force HQ had been disbanded and command of remaining operations returned to the Commanding General of the U.S. 1st Airlift Taskforce and the AOC of RAF No. 46 Group respectively.

The RAF ended their Airlift as they had started it: with a Dakota flight. The last Dakota of the Berlin Airlift landed in Berlin from Lübeck on Sept. 23 bearing the message on its nose: Psalm 21, Verse 11: For they intended evil against thee; they imagined a mischievous device, which they were not able to perform. One week later, on 30 September 1949 the last U.S. aircraft on the Airlift, appropriately a C-54, flew the last Airlift cargo into Berlin. The Airlift officially ended at midnight on that September 30.

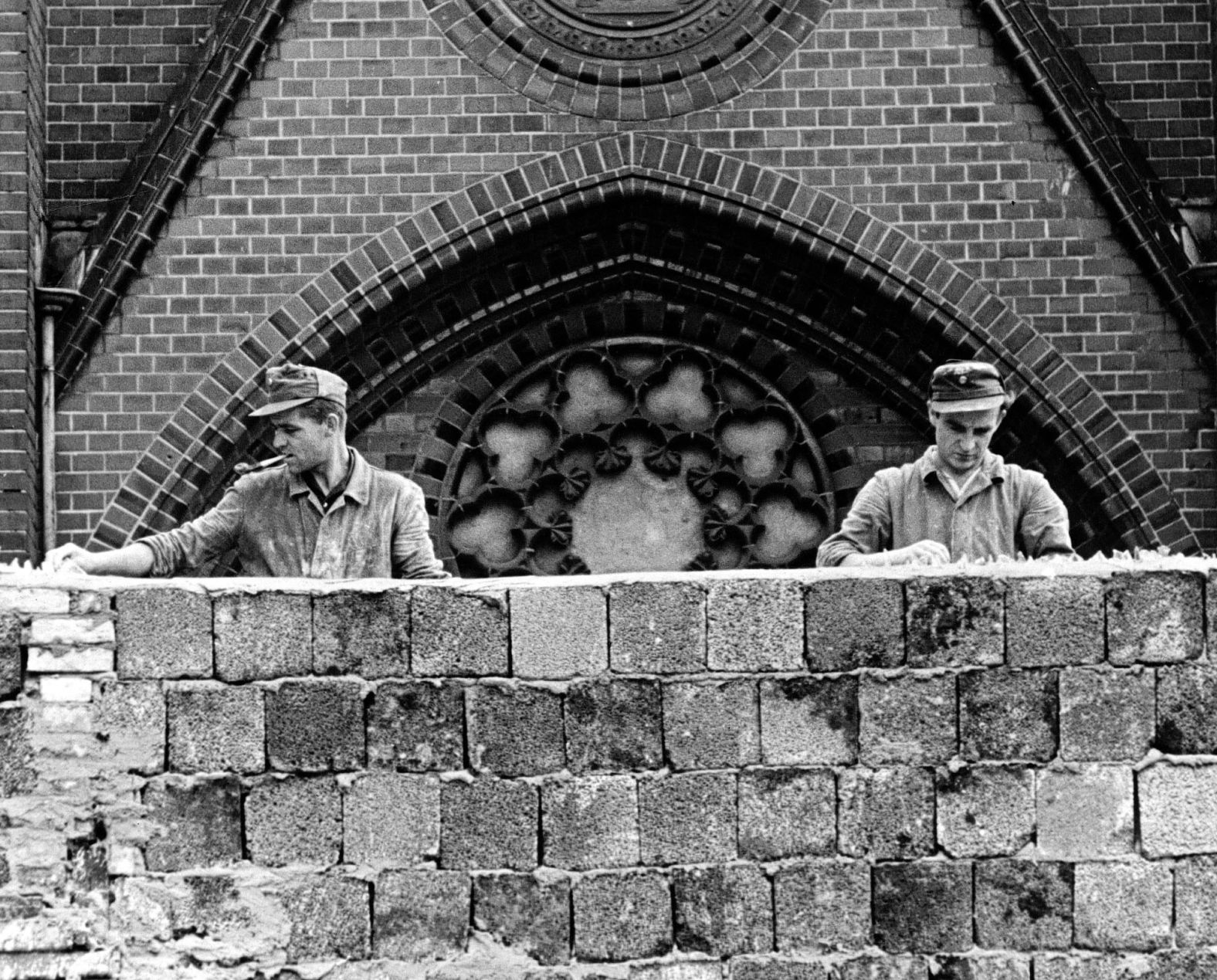

The Soviets continued to make sporadic attempts to put pressure on West Berlin throughout the rest of the Cold War. Khrushchev allegedly bragged that he had the West “by the balls” in Berlin and needed only to “squeeze” to make them squeal. He demanded troop withdrawals in 1958. In August 1961, he allowed a massive and militarily defended wall to be built around the Western Sectors of the city isolating it physically as well as politically. (Below an image of the Berlin Wall under construction.)

It was not until 1972, under his successor, that a Four Power Agreement finally “normalised” the situation in and around Berlin, but West Berlin was still enclosed in a wall and governed by Occupation Statutes as modified by agreements between the Victorious Powers of WWII. Berlin did not become an integral part of the Federal Republic of Germany until German Re-unification in 1990. (Below a picture of the Berlin Wall coming down in 1989.)

[i] Cited in Ann and John Tusa, The Berlin Airlift, Sarpedon, 1998, p. 370.

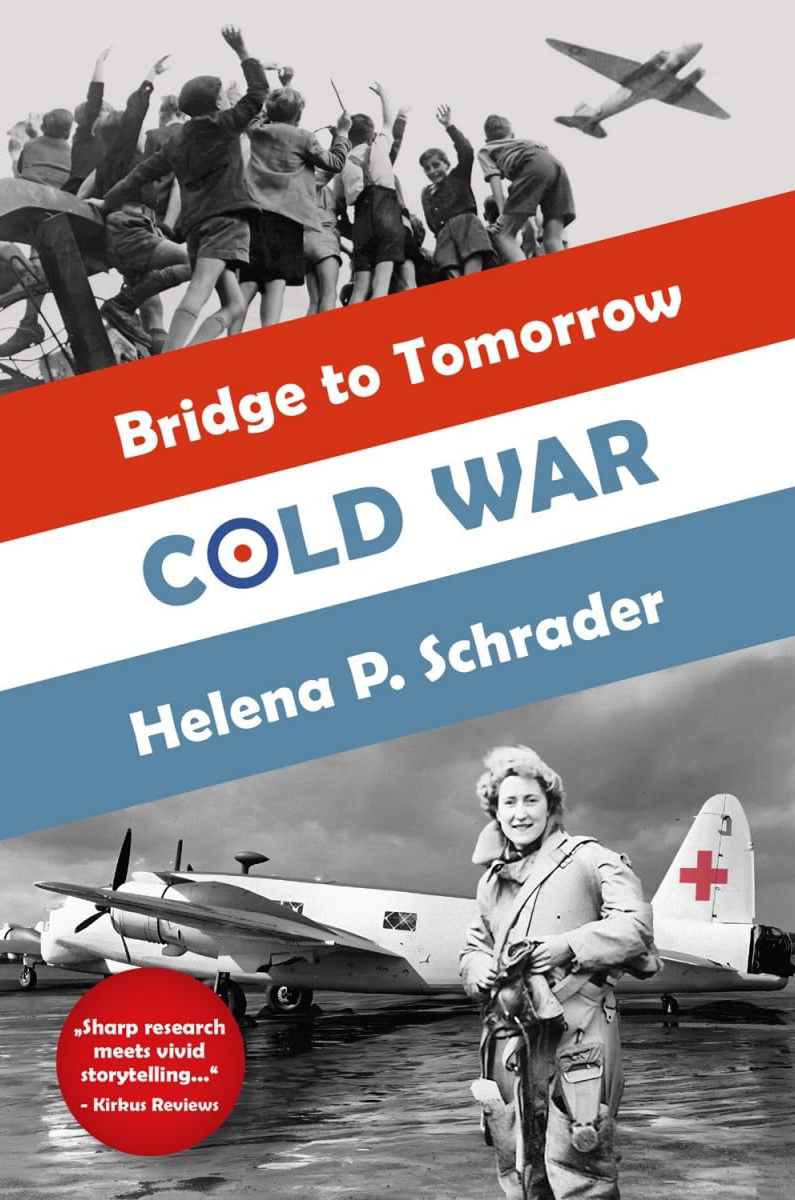

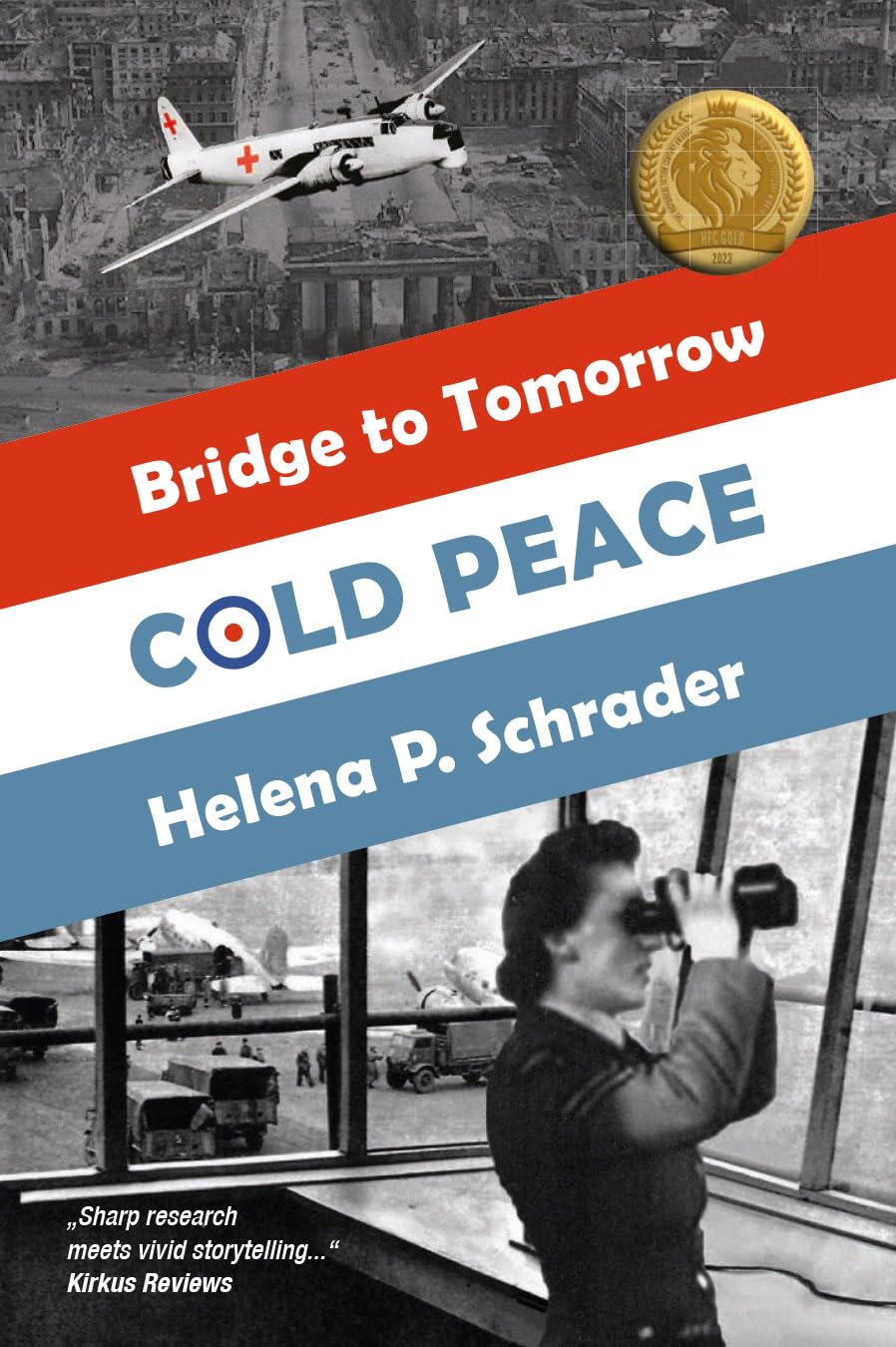

The Berlin Airlift is the subject of Bridge to Tomorrow, a trilogy of novels starting with Cold Peace and continuing with Cold War.

Watch a video teaser here: Winning a War with Milk, Coal and Chocolate

The first battle of the Cold War is about to begin….

Berlin 1948. In the ruins of Hitler’s capital, former RAF officers, a woman pilot, and the victim of Russian brutality form an air ambulance company. But the West is on a collision course with Stalin’s aggression and Berlin is about to become a flashpoint. World War Three is only a misstep away. Buy Now

Berlin is under siege. More than two million civilians must be supplied by air — or surrender to Stalin’s oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF Flight Lieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin. They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile, two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished and abandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on the side of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelist Helena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about how former enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how close the Berlin Airlift came to failing.

16 Responses

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

https://shorturl.fm/bUXBH

https://shorturl.fm/bkg5L

https://shorturl.fm/iLwGQ

https://shorturl.fm/qXqv4

https://shorturl.fm/pFimu

https://shorturl.fm/JLSac

https://shorturl.fm/ORPi9

Alright, ph987. Let’s be honest, it’s a mixed bag. Some things are great, others…not so much. They need to step up their game.

https://shorturl.fm/S4yEb

Share your unique link and cash in—join now!

That’s a great point about longshot value – often overlooked! Seeing platforms like jljl3 slot download cater to PHP & GCash makes betting so much easier for us here. Quick registration is a huge plus too! 👍

Yo! I checked out jii7777 and it’s alright. Solid, you know? It’s worth a look See for yourself right here: jii7777

Alright, just had a go at j88abcvip. I must say it is more complicated than other website, but not difficult. Check it out: j88abcvip

What’s up, everyone? I downloaded 51gameapp. It’s got a pretty gameplay. Check it out: 51gameapp